Updated: Oct. 6, 2020 at 2:08 p.m.

The majority-White area around GW has sustained one of the lowest coronavirus death rates among D.C.’s neighborhoods, especially compared to other areas of the city that are majority Black.

The city’s coronavirus case data show that three-quarters of people who have died from COVID-19 have been Black, despite making up just less than half of the city’s population. District officials and public health experts said the pandemic is unequally hitting marginalized communities because they face disproportionate access to essential services, like health care and education.

“It’s not an easy thing when you think about all of the realities that poor people face simply because they are poor, economically poor,” At-large D.C. Council member David Grosso said. “This is not easily solvable. The COVID emergency has actually kind of ripped off the band-aid and shown us all what the reality is for so many of our poor residents.”

Ilena Peng | Contributing Web Developer

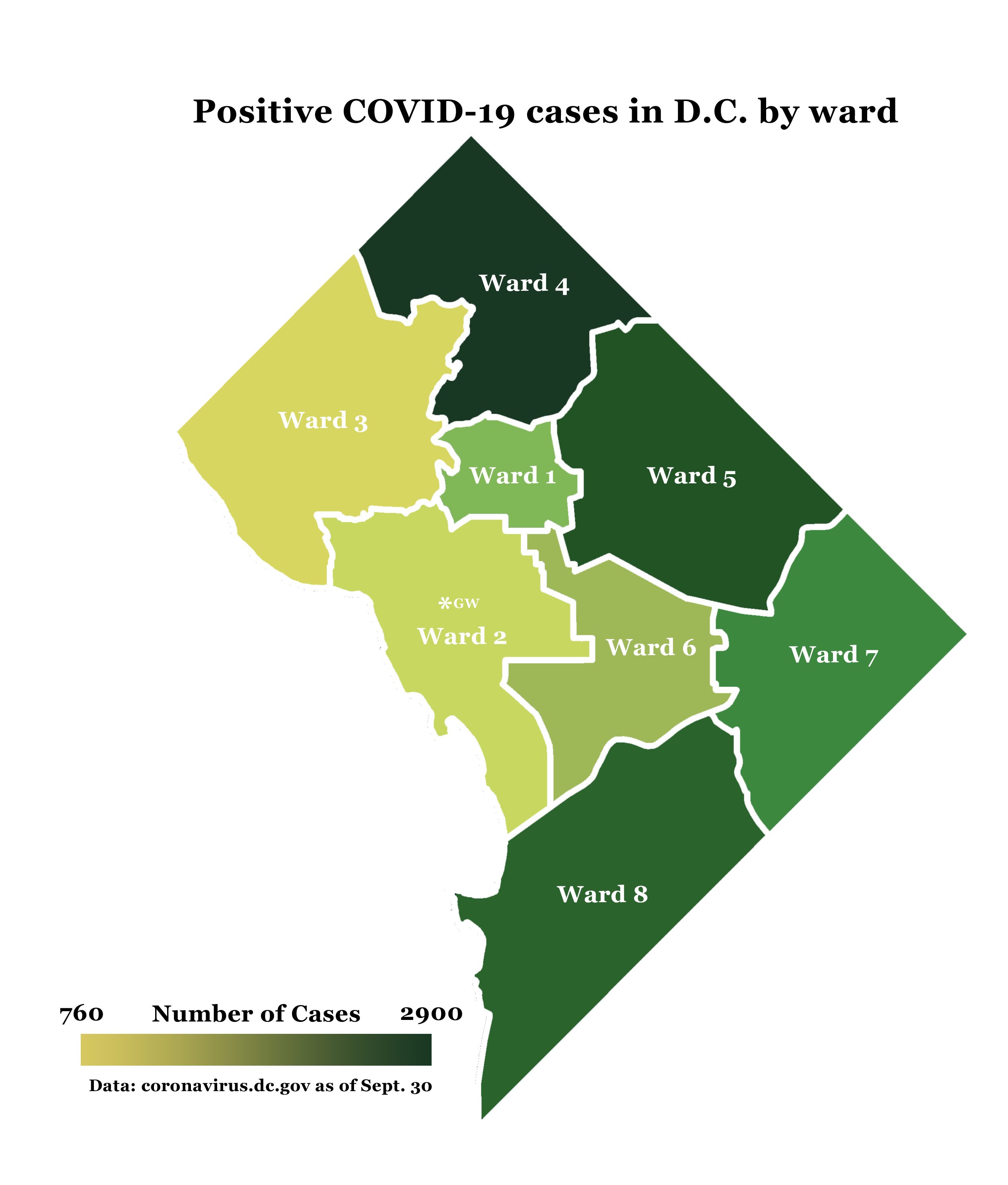

The majority of cases are concentrated in the northeastern, southeastern and southwestern parts of the city, where Black residents make up half or more of the population. Black residents constitute just over half of total positive COVID-19 cases in the District, and Hispanic residents comprise about a quarter of city-wide cases, according to the District’s COVID-19 website.

Ward 2’s 1,000 positive cases are the second-lowest number of positive cases of any ward, just below Ward 3, which logged 770 cases as of Sunday, according to the website. The neighborhood around GW, which includes Foggy Bottom and parts of West End and Dupont Circle, has tracked about 100 positive cases as of Sunday, placing the neighborhood in the bottom 10 in terms of positive coronavirus cases, the data show.

Ward 4 has been hit the hardest with COVID-19 cases, logging almost 3,000 positive cases as of Sunday, according to the website. Wards 5, 7 and 8 recorded just more than 2,000 cases each by Sunday, the website indicates.

Grosso said Black and Latino residents tend to work in essential services, like health care and food service, which have remained open throughout the pandemic. He said city officials have directed resources, like personal protective equipment and small business support, to essential workers in the city.

He added that many residents of color live in high density housing units, like apartments and public housing, that could lead to an increased risk of coming in contact with the virus.

“They have to show up to work, and they are our grocery line workers and working in our hospitals and other places where they couldn’t actually isolate themselves away from the virus like our more affluent White residents who tend to have more office jobs too,” Grosso said.

He said marginalized communities experience disproportionate access to transportation and grocery stores, another reason why the virus has hit those communities particularly hard.

He said government officials have taken strides to mitigate these disparities by prohibiting evictions and offering support for businesses who have been hurt financially amid the pandemic.

“We’ve provided more and more and more personal protective equipment, the PPE, for essential workers in the city,” Grosso said. “We’ve also tried to keep businesses from closing by supporting them. We’ve also prohibited evictions.”

The Council passed a complete eviction ban late last month, preventing landlords from ending rent agreements.

Grosso said some marginalized communities tend to lack trust in the health care system, which he said could be a result of not having the educational resources to navigate the system. He said city officials have publicized public health information through emails, newsletters and social media platforms, but it’s still an uphill battle to build trust and connect residents with a primary care physician.

“We also know that the education of folks has been something that we have not fully accomplished, and there’s huge disparities in our achievements at education and that lack of education,” Grosso said.

Alison Reeves, a spokesperson for the D.C. Department of Health, said Mayor Muriel Bowser is working on private sector partnerships, like a new Howard University hospital and a Universal Health Services-run hospital at the St. Elizabeth’s campus in Southeast D.C., which aim to improve equity throughout the District.

“The District continues to be forward-looking, leveraging public investments in partnership with the private sector that will support major investments over the next five years,” Reeves said in an email.

Public health experts said racism is deeply rooted in public health issues throughout the United States and government officials should take strides to address the issue when devising solutions to the coronavirus pandemic.

Cities like Milwaukee and New York have seen similar racial disparities in their coronavirus case data, according to a New York Times report from this summer. The same report revealed that nationwide, Black and Latino residents are three times more likely to contract the virus than White residents.

Tyan Dominguez, a clinical professor of social work at the University of Southern California, said marginalized communities tend to lack trust in the health care system because they have historically lacked access to health care and faced disparities in quality of care based on race.

“These are systemic issues, it’s not a silver bullet solution and it’s not something that is going to be fixable overnight,” Dominguez said. “It’s a multi-pronged issue from the longstanding history, and I think it’s going to take a multi-pronged approach and consistency in what responses are within the system.”

Camara Jones, the former president of the American Public Health Association, said the national response to the pandemic has been focused on medical care, when pandemic response officials should treat it as a public health issue.

She said paid sick leave, a universal basic income and a living minimum wage would help mitigate disparities in public health outcomes. She said investing in housing, green spaces and schools for communities of color would also help reduce public health disparities.

“There’s no basis in the human genome for racial subspeciation,” Jones said. “We know it’s not a gene, but it’s not even our choices.”

Nicholas Anastacio contributed reporting.

This post has been updated to correct the following:

The Hatchet incorrectly reported that the new hospital at the St. Elizabeth’s campus will be run by GW. Universal Health Services, the majority owner of the GW Hospital, will run the facility. We regret this error.