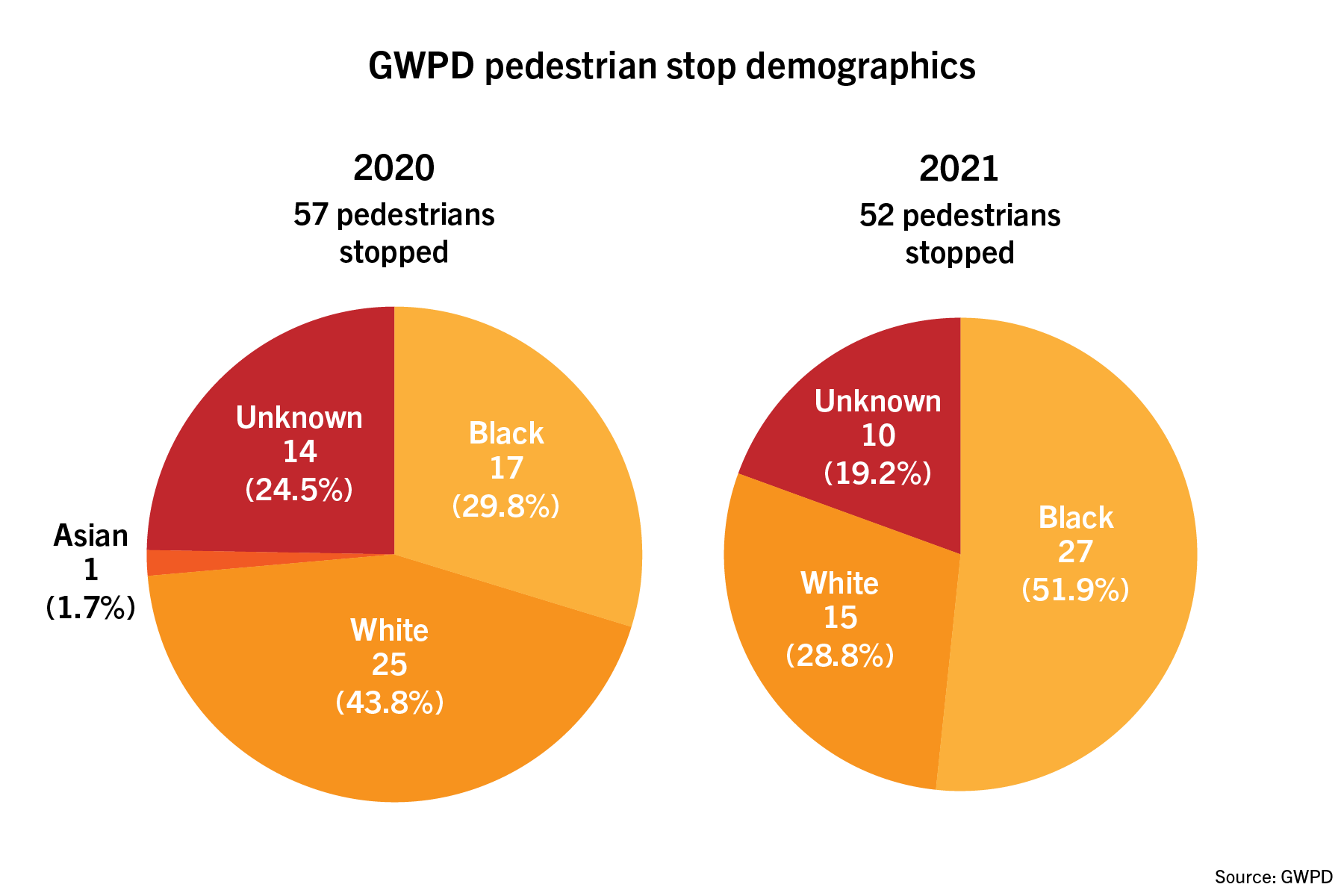

GW Police Department’s pedestrian stops dropped in 2021 despite the University’s campus reopening, but officers stopped a greater percentage of Black pedestrians than other racial demographics, according to a GWPD report issued earlier this month.

GWPD released its second annual report on the ethnic, racial and gender demographics of the pedestrians that officers stopped earlier this month, which stated that officers stopped 52 pedestrians in 28 total stops in 2021 – a drop from 57 pedestrians in 2020. The report states 27 stopped pedestrians were Black, 15 were white and the race of the other 10 were unknown.

Male pedestrians accounted for 37 of the stopped pedestrians, while officers stopped 14 female pedestrians. One pedestrian’s gender was unknown to officers.

GWPD Chief James Tate said the drop in stops from 2020 to 2021 is “hard to judge” because the sample sizes are limited to those two years. He said GWPD may take about three years to better interact with the data to understand the GW community, but he was still happy to release the data on a yearly basis for transparency.

“I’m still proud of the fact that we’re sharing that because I think it’s important when it comes to transparency and accountability with our community,” he said.

GWPD released its first demographic data report last April after demonstrations protesting the killings of unarmed Black people like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Daunte Wright pushed police departments to start instituting reforms in 2020. The department released the report days before Derek Chauvin – the former Minneapolis police officer who murdered George Floyd after kneeling on his neck for several minutes – was convicted of second- and third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter.

Nicholas Anastacio | Graphics Editor

The number of Black pedestrians that GWPD stopped in 2021 climbed by 10 people. Tate said searches of pedestrians who fit the description of the suspect in the G Street Garage assault in October and stops tied to unlawful entry reports at residence halls could have accounted for the jump.

“We had a number of reports of unlawful entry into the residence hall early on in the fall,” Tate said. “And that required us to be much more vigilant in trying to find individuals that are described to us in terms of the description.”

Of the 28 stops, GWPD officers used force three times, according to the report.

GWPD officers opened an investigation into one of the three incidents, stemming from a November pedestrian stop of an individual who reportedly walked in and out of traffic, which led to a foot pursuit and deployment of pepper spray before the subject’s arrest. They investigated the use of force and disciplined the officer, but Tate declined to say how the officer was disciplined.

Tate said officers should have a suspicion of a crime before initiating a foot chase, and GWPD determined the officer did not have reasonable suspicion when the officer began to chase the subject.

“You have to have reasonable suspicion that some sort of crime has been committed before you initiate the foot pursuit,” Tate said. “And in that case, the supervisor that night very quickly realized that we didn’t have that in that case.”

Tate said when an officer uses any level of force – like forcibly putting handcuffs on a person – the officer must fill out a form that details the situation and amount of force used. GWPD’s defensive tactics instructors then review the form, which the officer’s captain and Tate approves if the use of force is determined to be justified.

“If there’s a problem anywhere in the process that’s concerning that our officer may have violated policy, then there is a pause and an investigation is initiated,” Tate said.

Tate said GWPD has made a “tremendous amount of progress” in furthering community outreach among students and student organizations, and the department is currently planning two community outreach events, which he said will be part of some of GWPD’s largest-ever outreach initiatives.

Tate said the student reception to the released data has been generally positive. He said students asked clarifying questions about the specifics of the race and gender breakdown of the data and appreciated the transparency of the demographics data, which he said was critical in building trust with students.

“Since 2020, I am pleased with the feedback that I typically receive regarding our transparency and efforts to work with the community and community engagement,” Tate said. “So we’ve come a long way. I also think we have a very long way to go.”

John Sloan III, a professor emeritus in the department of criminal justice at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in an email that GWPD’s released data was “problematic” because the limited sample size did not allow for comparisons between stops that could reveal “larger patterns” within the data. He said the data should record the races and genders of pedestrian stops of multiple people and should include factors related to the stops like probable cause and pedestrian consent.

“These reports may seem like an attempt at increased transparency but the problems associated with the way the data are presented results in just the opposite – continued opacity,” Sloan said in the email.

Michael DeValve, an assistant professor of criminal justice at Bridgewater State University, said campus police departments regularly release demographic data about their stops, but GWPD’s data should be more descriptive to align with their standards. He said he would have preferred to see more information about the nature of the stops themselves, like the reasoning behind the stops.

“As a criminologist, I’d be curious to know more about what those look like,” DeValve said. “Because those are slightly more of an imposition because then they involve a degree of detaining so the person is not free to leave.”

DeValve said he would be “hesitant” to draw conclusions from the ethnic and racial elements of data because of the relatively small sample size of the people stopped. He said GWPD could use the data to ask questions and better assess their practices, but only if trust exists between students and the department.

“It’s a place to begin, and if that conversation is a trustful one, it’s a place to begin dialogue,” DeValve said. “If not, you’re going to have to take a different strategy.”

Jared Gans, Talia Miller and Zach Blackburn contributed reporting.