Updated: April 19, 2022 at 1:44 p.m.

Latino adolescents’ mental health and academic performance declined during the COVID-19 pandemic as parents’ job loss and teenagers’ childcare responsibilities increased, according to a study from Milken Institute School of Public Health faculty published earlier this month.

A team of four professors found that 10 percent of Latino families encountered COVID-19 hospitalization and nearly 50 percent of Latino parents experienced job and income loss, factors that caused increased stress among Latino youth. More than 60 percent of Latino teenagers took over childcare responsibilities from their parents, which contributed to low academic performance, depression and isolation from friends, according to the study.

The team surveyed more than 500 Latino students from middle schools in a Georgia school district between fall 2018 and spring 2021.

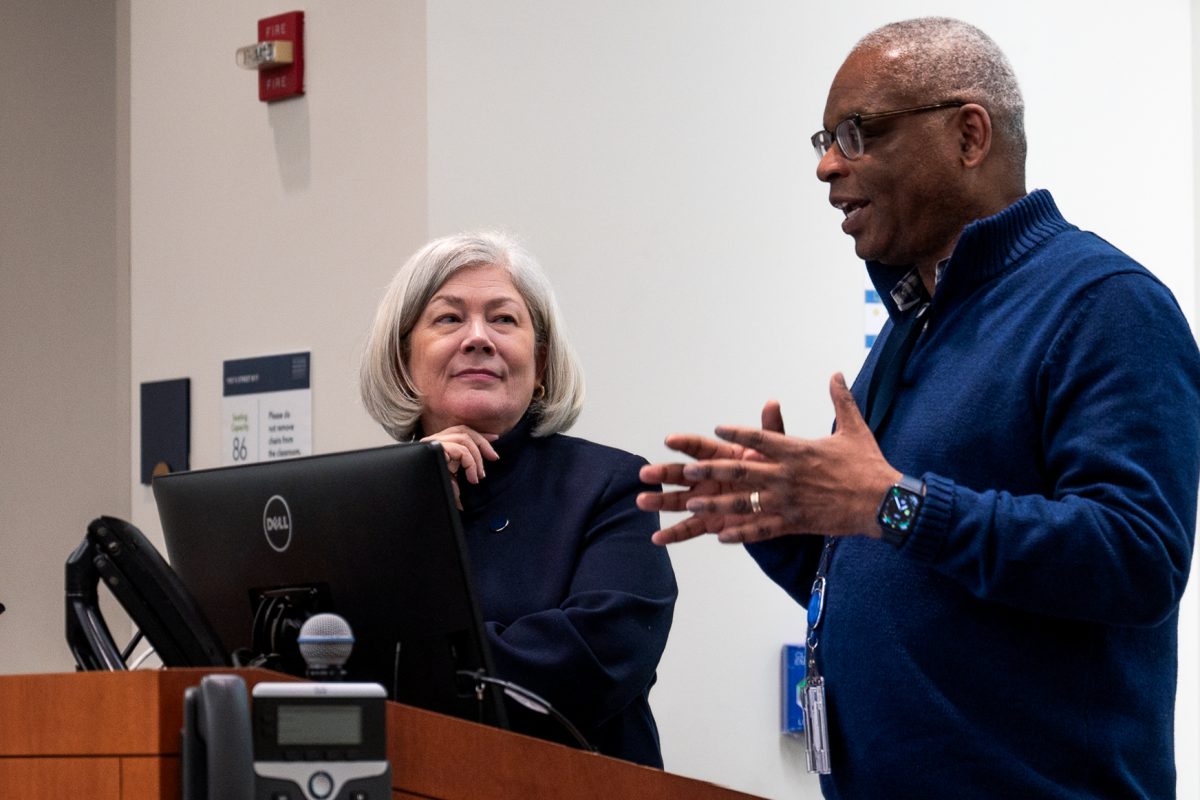

Kathleen Roche, the study’s lead researcher and a professor of prevention and community health, said adolescents were more likely to report taking on childcare responsibilities if they also reported health and economic stressors like a family member’s COVID-19 hospitalization.

“I will say that this study provides some of the first empirical evidence to document important harms conferred by the pandemic and having that empirical data is really important for our understanding of things to look out for in terms of areas of need for today’s young people,” she said.

Roche said the study can prompt other organizations to create preventive interventions and policies to improve Latino adolescents’ lives and conduct more research on how other factors of the pandemic affected Latino youths’ development.

She said the study is part of an eight-year research project following the understudied Latino youth population and their mental health from middle school to early adult years, a project launched in 2018.

The team compared Latino teenagers’ survey results from fall 2020 and spring 2021 to previous surveys completed in fall 2018 and fall 2019 to observe changes in mental states and childcare responsibilities before and during the pandemic, according to the study.

Roche added that prior research studies regarding Latino youths’ mental health didn’t factor in stressors like job and income loss and COVID-19 hospitalization.

“Taking care of kids doesn’t seem like that big of a deal to ask a teenager to do, but it’s important to realize that it is actually a very meaningful change in their lives that may have interfered with very important aspects of development during the teenage years that these kids didn’t get to experience,” Roche said.

She said shifting childcare responsibilities onto Latino teenagers during the pandemic caused heightened levels of anxiety and depression, drops in grade point averages and increased behavioral issues like aggressive tendencies in school settings. She said Latino teenagers’ behavioral problems during the pandemic can make transitioning into adulthood more difficult because teachers can inappropriately label them as “problem children,” which punishes them for their actions instead of helping them.

Roche said teenagers taking more time out of school to care for family members can also contribute to a lower likelihood of attending higher education and attaining economic independence in their adult years.

“It’s also important for policy and communities to be able to support families who experience health and economic and childcare strains because that can help mitigate risks to adolescents,” she said. “The risks I describe will have lasting effects into adulthood. They don’t just end with the end of the teenage years.”

David Huebner, one of the study’s four co-authors and a professor of prevention and community health, said he helped Roche formulate questions related to COVID-19 stressors for the surveys, like the number of COVID-19 related hospitalizations within a Latino household and the surge in childcare responsibilities because of hospitalizations or other pandemic-related circumstances.

He said a greater investment in public health before the pandemic could have lessened the stress on the Latino population because public health officials would have been more prepared to respond with solutions to pandemic-related problems.

Huebner said the pandemic disproportionately affects marginalized communities with factors like hospitalizations of family members and deaths as well as environmental issues like neighborhood violence and economic hardships, which researchers should take into account when conducting studies on minority groups like Latinos.

He said the study can show teachers that increasing the flexibility of academic work will ease the strain some students feel because of childcare responsibilities.

“I think that the best thing we can do is to make sure the people who provide care and services to these kids are aware of the impact COVID has had on them so they can make the decisions about their care and their education in a way that is mindful of the significant impact that COVID has had,” Huebner said.

This post was updated to correct the following:

The Hatchet incorrectly reported that Roche said the study is some of the first “imperial” evidence of documenting the harms of the pandemic on adolescents. She said it was some of the first “empirical” evidence. We regret this error.