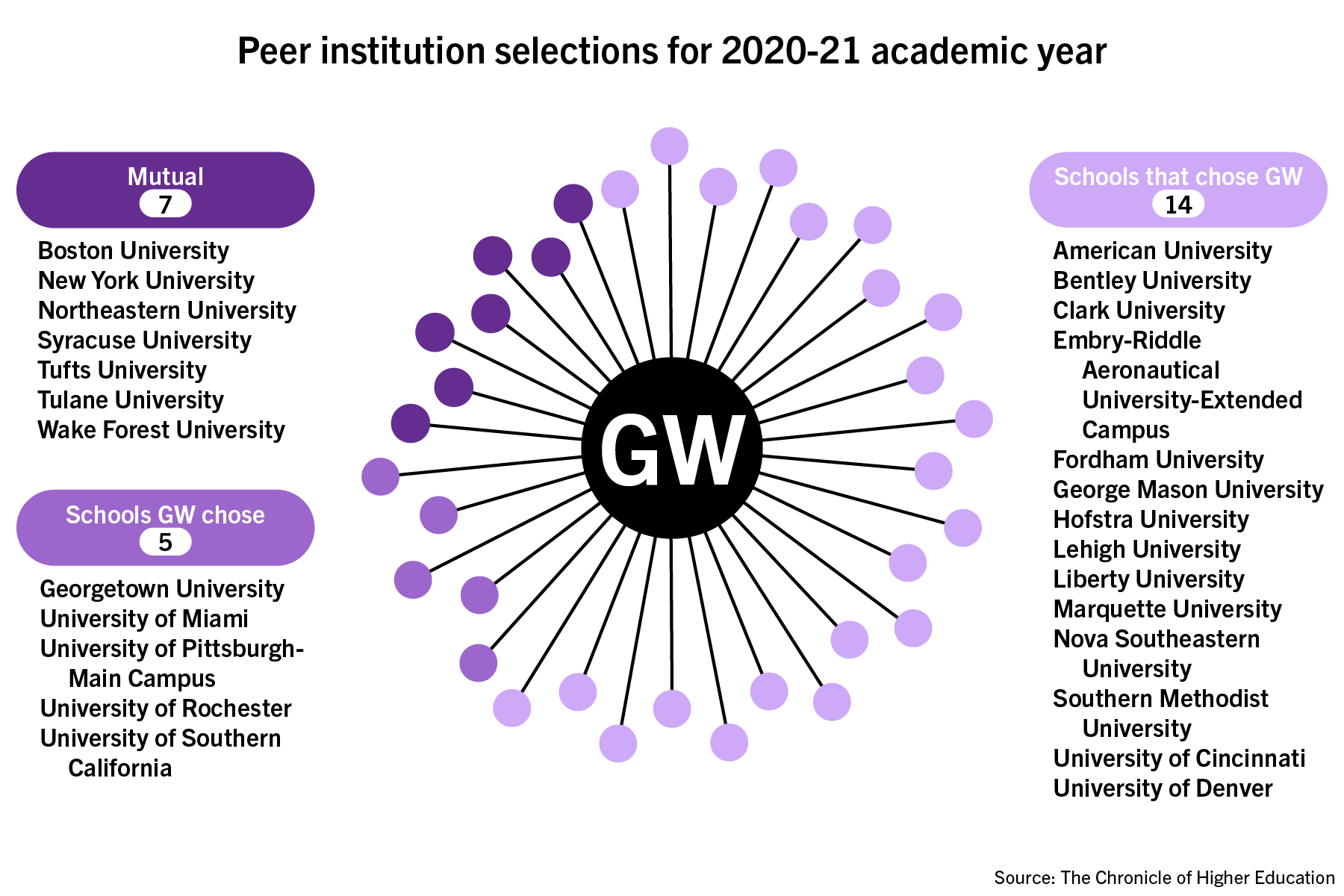

Five of the University’s 12 peer institutions don’t consider GW as one of their peers, according to a report from the Chronicle of Higher Education published late last month.

U.S. News and World Report currently ranks GW lower than all 12 of the schools that it considers its peers, despite the University rising three spots last year. Experts in higher education administration said GW’s peer school list is likely a combination of schools that officials consider to be similarly academically ranked and more selective institutions that they “aspire” to be ranked closer to in the coming years.

Higher education institutions submit their peer schools to the Education Department’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System each year to receive data that compares their performance to their selected peers.

Officials shaved six schools from its peer school list in 2018 when then-University President Thomas LeBlanc arrived at GW as a part of his early strategic planning.

Fourteen schools, including Fordham and Liberty universities, consider GW to be one of their peers – but GW doesn’t include them in its list.

Nicholas Anastacio | Graphics Editor

Mary Churchill, the associate dean of strategic initiatives and community engagement at Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education & Human Development, said many universities will list both schools that they consider their “peers” and “peer aspirant,” which they are aiming to be ranked alongside, when determining their peer lists and strategic planning.

“If it’s about the rankings, and especially U.S. News and World rankings, I do think institutions are much more likely to indicate peers that are higher ranked than they are those that are lower ranked,” she said.

Churchill said GW and BU would likely come up with their peer school lists in a similar fashion since they’re both “highly selective institutions.”

GW’s overall acceptance rate is about 43 percent, while BU’s is just about 20 percent, according to data collected by U.S. News and World Report.

“I think the higher up you are in the U.S. News and World Rankings, the lower the number of peers you’re going to put in your list,” she said.

Churchill said new university leaders will often receive instructions from their boards of trustees to make changes to their peer school lists if the institution needs a new strategic plan because officials will use peer schools ranked above them to formulate policies to help rise in the rankings.

“So if the board is interested in hiring someone to shake it up, then yes, and the board would indicate that, probably even in the job description and with a search firm, like ‘We’re looking for someone who’s going to shake this up,’” she said.

GW has lacked a long-term strategic plan since officials labeled GW’s last strategic plan as “obsolete” because of the COVID-19 pandemic in November 2020. Professors said officials should focus on including faculty voices in major decision-making before creating a new strategic plan during interim University President Mark Wrighton’s maximum term of 18 months.

Jarrett Gupton, an assistant professor of higher education and student affairs at the University of South Florida, said most university leaders will use factors like campus setting and location, enrollment data, research funding and rankings from organizations like U.S. News and World Report when coming up with their peer lists.

He said many administrators will try to consult with stakeholders, like faculty and investors, when forming with their peer school lists to make sure the newly listed institutions align with the community’s sentiments about their school and the standards that community members want to see.

Gupton said most colleges and universities will look to change or alter their peer school lists every five to 10 years, but new university leadership will often look to change the peer list.

“If you see the presidential change or you see a committee look at strategic goals, and that will probably see changes to the peer list coming your way, because every five to 10 years, there’s generally a shake up – a need for the university to assess itself and what it will need in the future,” he said.

LeBlanc retired from GW at the end of last semester and was succeeded by Wrighton to serve for up to 18 months while officials look for a permanent president. Provost Chris Bracey was appointed to the permanent role in February after coming into office last year when he took over from Brian Blake at the end of last academic year.

Everrett Smith, an assistant professor of higher education at the University of Cincinnati, said although the pandemic affected long-term university strategic planning across the nation, peer school lists likely didn’t change as much as they might have before the pandemic.

He said changes in the higher education landscape during the pandemic – like moves toward online learning – and the duration of those pandemic-related measures will help determine how universities compare themselves to others.

“I don’t know yet that that peer institution list shifts all that much over a course of 24 months,” he said. “Especially when it comes to rankings, it is incredibly hard to move up in the rankings.”

Smith said officials should try to reassess their peer school lists once a year to align with any changes in the industry or their institutions. He said officials reviewing their lists annually can help shape strategic planning for the institution in the long-term.

“You look at the U.S. News World Report, those rankings are annual, as an example,” he said. “And so you probably want to be consistent with these kinds of industry rankings.”

Jennifer Snyder – the manager of the Higher Education Consortia, a research organization at the University of Delaware – said many pairs of peer schools will have separate peer lists because of the thousands of differing characteristics, like location or staff salaries, among institutions.

Snyder said the peer school research from the Chronicle of Higher Education will provide an outline for university officials across the country to see which schools have similar characteristics or rankings, allowing them to compare each other more effectively.

“It helps institutions see beyond what they’ve long considered their standard group of peers,” she said. “It allows for additional exploration, and I think that looking at more benchmarks and looking at as many different groups of peers as possible can only benefit administrators as they’re making decisions.”