Experts said the nearly 4 percent increase in undergraduate tuition for the upcoming academic year is the result of inflation and pandemic-related costs, like isolation housing and COVID-19 testing.

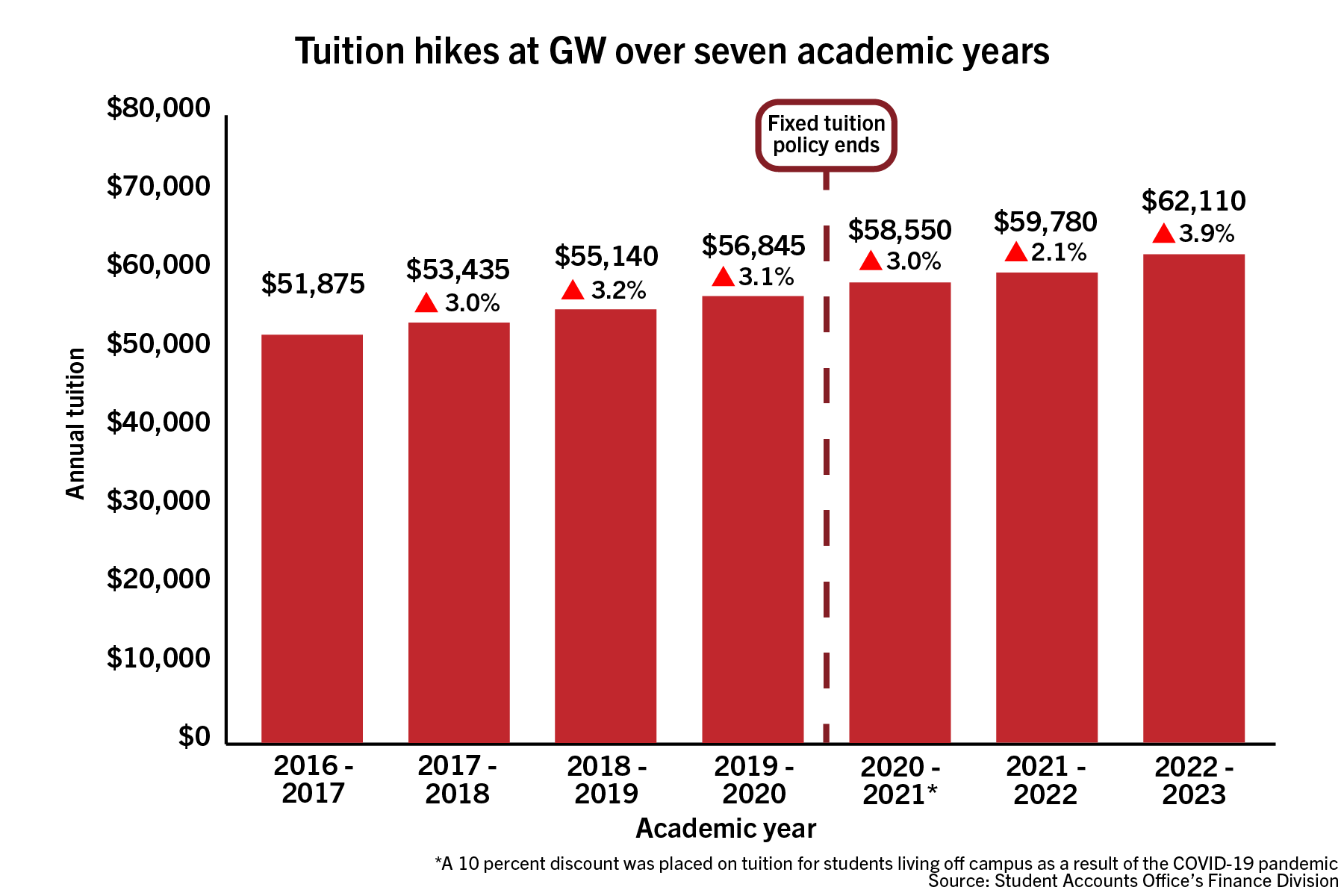

Officials announced Thursday that GW’s cost of attendance will surpass $80,000 for most undergraduates for the first time next academic year, with undergraduate tuition for those who entered GW in fall 2020 or later increasing from $59,780 to $62,110. Jay Goff, the vice provost for enrollment and student success, said officials calculated the tuition increase based on costs that may have risen due to inflation “across the board,” like personnel and utilities.

“We don’t anticipate any significant changes in enrollment due to the cost increases, and that’s largely due to the fact that we will also adjust financial aid packages to assist students with higher financial need,” Goff said in an interview last week.

The University launched a “focused initiative” in October to increase the financial aid budget for Pell-eligible students to fund need-based grants, loans and work-study packages.

Nicholas Anastacio | Graphics Editor

Officials ended GW’s fixed tuition policy starting with the Class of 2024, a move that experts said would help align the University with its 12 peer schools that have implemented similar policies.

The Class of 2022 is the largest freshman class at GW since 2008, but Goff said their graduation this year was not a factor in the tuition increase for the upcoming academic year. He said officials don’t plan to expand the size of the Class of 2026.

“With the additional seats and beds available, we hope to offer new transfer student seats both in the fall 2022 and spring 2023,” he said.

Jared Abramson, the vice president for financial planning and operations, said in January that COVID-19 testing costs have persisted as one of the “major impacts” on the University’s finances during the current fiscal year. A Faculty Senate report from November states that fiscal year 2021 pandemic-related costs were projected to drop from $17.9 million to $8.4 million in fiscal year 2022.

Officials chose to split the $14 million that the University received from the second round of federal stimulus funding last March between student aid and institutional costs related to GW’s COVID-19 testing apparatus.

“The general increases in operational costs and materials definitely played a role in having a slightly higher rate,” Goff said.

Undergraduate tuition for the upcoming academic year marks a nearly 4 percent increase, the highest in at least four years. The previous academic year was the first when incoming students were not eligible for the fixed tuition policy, but officials offered a 10 percent tuition discount for all students not living on campus in light of classes being held online.

“There was a small increase, kind of similar to where we are this year, that was planned, but it was offset by the 10 percent reduction,” Goff said.

Experts in higher education said University leaders should increase the need-based aid they offer to students to ensure that the increase in tuition does not correspond to a drop in enrollment.

Sandy Baum, a senior fellow in the Income and Benefits Policy Center at the Urban Institute and a former professor of economics at Skidmore College in New York, said the recent rise of inflation also corresponded to an increase in labor costs, which is why colleges are likely increasing their costs of attendance.

Last month, U.S. inflation rose to a four-decade high at an annual rate of 7.5 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This rise has led to a surge in prices of utilities, housing, groceries and health care, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Baum said officials should focus on building up those financial aid policies for students from lower-income families.

“What matters the most to students is really what they’re doing with their financial aid policies and how much aid they’re giving to students whose families have really limited financial capacity,” she said. “If what you’re worried about is access to the institution, that’s what you should be thinking about – not what happens to the sticker price – but what happens to the prices that individual students with different income levels actually have to pay.”

Michael Hansen, a senior fellow at the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institute, said officials across higher education institutions are looking to use higher revenue from tuition to cover expenses intended to mitigate the pandemic.

“They have been increasing their cost of operation because they’ve been doing extra higher levels of sanitation than they’ve had in the past, than they would typically do during nonpandemic times – extra janitorial services more so than previously, supplying kids with masks and hand sanitizer, those types of things,” he said.

Trustee Ellen Zane said at a Board of Trustees meeting in October that officials broke even in the fiscal year 2022 budget after implementing budget mitigation measures to limit the pandemic’s financial impact.

Hansen said the higher tuition could dock enrollment rates and deter students from lower-income backgrounds from continuing their college education.

“It does tend to be the case that students do often choose to stop out whenever they’re feeling higher levels of financial stress or financial instability and when they do stop out there’s a decent share of people who just don’t come back,” he said.

Officials said in October that total enrollment fell by 2.1 percent, marking the slowdown of a multi-year decline in enrollment.

Sophia Nguyen, a policy analyst with the education policy program at the think tank New America, said in light of the labor shortage during the pandemic, university leaders are looking to improve their employee benefits like health care to ensure that they are able to fill empty staff positions.

More than 47 million workers left their jobs during 2021 as part of the “great resignation,” according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

“Colleges have to go out of their way to maybe find staff and maybe have a better benefit for them,” she said. “I would say inflation and the current labor shortage can likely explain the tuition increase that you’ve seen this year.”

Daniel Patrick Galgano contributed reporting.