Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer emphasized the role that participation and persuasion plays in a democracy at a speaker event Thursday.

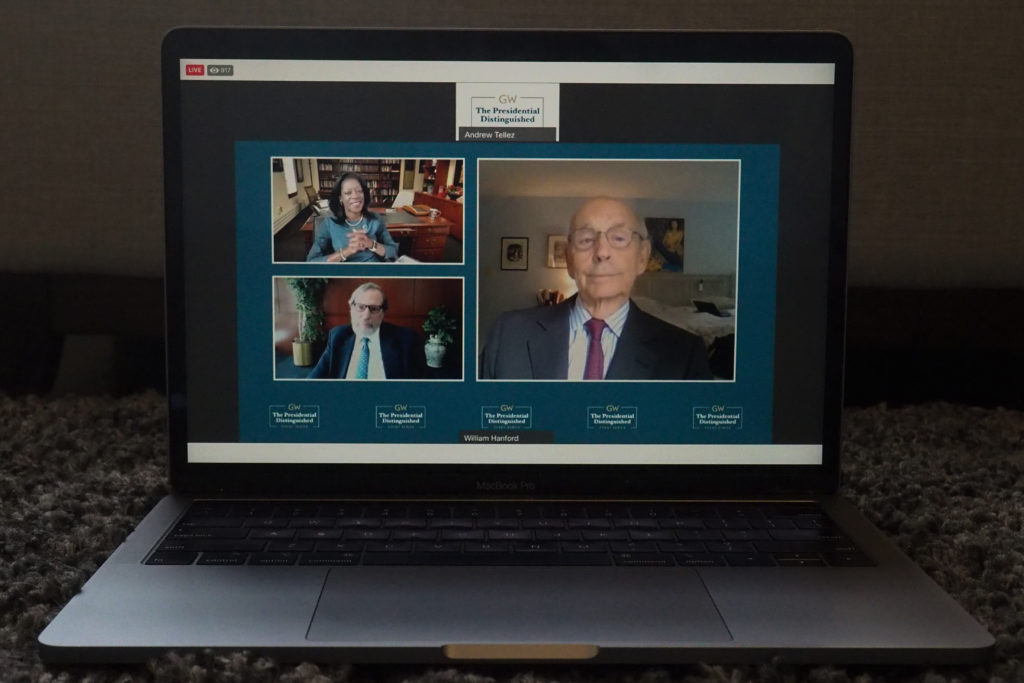

Breyer – one of the court’s left-leaning associate justices – discussed the value of the U.S. Constitution and the role activism plays in preserving the document. GW Law Dean Dayna Bowen Matthew and Associate Dean Alan Morrison moderated the event, which fell on the anniversary of the signing of the Constitution in 1787 in Philadelphia.

Breyer, who will enter his 27th year on the court next term, urged students throughout the event to get involved in their communities to turn the opinion of voters and help overcome the issues the country faces today.

“Stop complaining and start convincing,” Breyer said. “What are you doing about it?”

University President Thomas LeBlanc delivered brief introductory remarks at the event, this fall’s kick-off event of the Presidential Distinguished Speaker Series. Almost 1,000 people attended the virtual event, held on Facebook Live.

Breyer paid homage to some of the documents and schools of thought that laid the foundation for equal protection and the rule of law under the Constitution. He highlighted the Magna Carta, an English document signed in 1215 limiting the monarchy’s power over the execution of justice.

“The great thing about the Magna Carta, which the barons forced on King John, was that it said, ‘Due process of law – that means King John,’” Breyer said. ‘You have to follow the law too.’ And every one of us has that protection. And it’s that very basic legal principle that is the rule of law.”

Breyer also spelled out the limits of the courts as an institution charged with protecting the rule of law and justice, citing fights against integration of schools as evidence that the Supreme Court’s orders – as in the case of Brown v. Board of Education – can be defied.

“Go back to Brown – I finished college five or six years after Brown,” he said. “You know how much integration there was in the South? Not much. Brown was in 1954. You know what happened in 1955? Nothing. Next to nothing. 1956? Nothing.”

Ultimately, the slow march of integration brought to the forefront Alexander Hamilton’s remarks about the courts’ lack of coercive power through money or the military, Breyer said.

“They don’t have the purse, and they don’t have the sword,” he said.

He reiterated that courts must, as citizens do, persuade parties to follow their judgments through the power of their arguments.

“Convince people that your decisions are fair and just, and then they might respect that leadership, then they’ll follow it,” he said. “There are ups and downs, but I think that’s probably the best way, and it may be the only way.”

Before his appointment to the court, Breyer taught law at his alma mater, Harvard Law School, and served as a lawyer at the U.S. Department of Justice and for the Senate Judiciary Committee. Former President Jimmy Carter appointed Breyer to the First Circuit Court of Appeals in 1980, and former President Bill Clinton appointed him to the Supreme Court in 1994.

Breyer said working for the Senate Judiciary Committee gave him a sense of how an institution governed by politics and ideology reaches decisions – which Breyer said was far from how Supreme Court justices operate. He said differences in opinion among justices are rarely partisan or ideological in nature but more often the product of how valuable each justice considers each potential source of interpretation.

“There’s text, there’s history, there’s tradition, there’s precedent, there are values and purposes and there are consequences,” Breyer said. “Those are elements and tools that judges use to interpret words in the text of the statute or the Constitution. All of those play a role. Some put more weight on the one, some put more weight on the other.”

Because Americans rarely engage with Supreme Court opinions and dissents directly – instead receiving information about the court through commentators in the media – they often have an erroneous idea that justices are “junior-league politicians,” he said.

At the end of the event, Breyer reiterated his call for Americans to reach decisions by consensus rather than conflict.

“Remember those joint projects,” he said. “Remember working on the school board with other people. Remember working on the library committee of something or the other. Remember working on some jobs creation agency. Remember that working with other people requires cooperation and compromise. And the court is no exception.”