A biomedical engineering professor is using his science background to preserve historical archives.

Murray Loew, a professor of biomedical engineering, is researching how deteriorating glass affects early 19th-century flutes. He said studying crystal flutes can be used to determine a strategy to retroactively stop deterioration – a widespread problem that museums and collectors have run into.

Loew began the project to aid curators at the Library of Congress who realized a collection of glass flutes on display were worsening in condition, cracking and flaking. The flutes that are being examined were made in the early 1800s by Claude Laurent, a Parisian watchmaker and mechanic, who became known for his novelty crystal flutes.

Loew said while there is limited known history about Laurent’s workshop or why the flutes were built, the objects gained traction within communities of collectors because of their intricacy. Some of the specialty flutes were gifted to prominent historical figures like James Madison and Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Library of Congress currently has about 20 of Laurent’s flutes, including the one gifted to Madison, on display.

“The historical value is in their workmanship,” Loew said. “Some are in good shape and some are in terrible shape, but that’s OK because we’ll be able to use some of them for some studies.”

While Loew is using the flutes as a testing ground to learn how glass deteriorates over time, the objects are just the beginning. Loew said he will use his findings to examine tens of thousands of glass plate negatives – which were used to develop film during the Civil War era – to prevent the erasure of thousands of images from this time period.

Loew is now working with the Library of Congress and Catholic University to request funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities to continue their study of glass at risk.

Through his research, Loew found that the composition of the glass – like if it contains lead or not – affects how quickly or slowly it will deteriorate over time.

“The idea was if you could determine, ideally non-invasively, which of your glass objects was at the risk of further deterioration, you then would be able to take some measures to slow down or stop further deterioration,” Loew said.

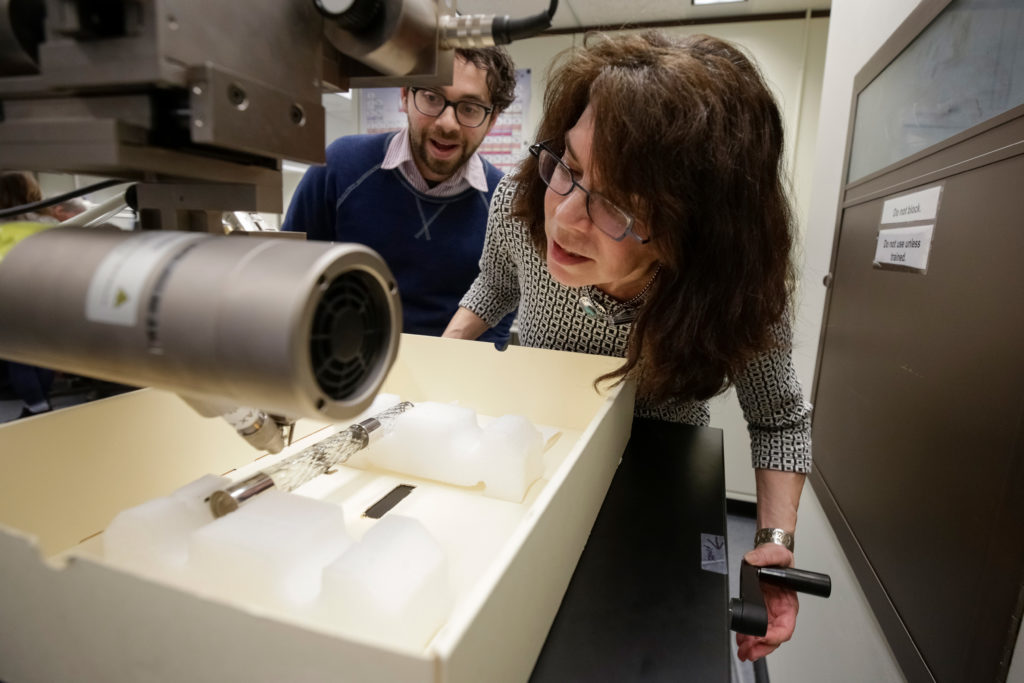

The researchers removed less than a gram of glass off of several of the flutes, analyzed the sample and recreated glass formulas that replicated the flutes. From there, the recreated glass formulas are placed into aging chambers where they are artificially aged through exposure to high temperatures and humidity.

“By accelerating the aging, you get some idea of what the flutes would have gone through under normal aging conditions,” Loew said.

Loew said that it’s common for smaller museums and collectors to improperly store artifacts for decades due to a lack of space, funds and other resources. He said the way glass artifacts are stored may be impacting how quickly the glass deteriorates.

Loew said he hopes his research will lead to developing tools that will assist small historical societies and museums in determining the status of their own glass artifacts.

The team of researchers hopes to create a relatively easy and inexpensive technique for these small-scale groups, which Loew called a “decision tree.”

This series of steps, put together by Loew and his research team, would allow museums and historical societies to use tools like an ultraviolet flashlight or a small X-ray system – both of which can be used to detect problems in glass – to independently determine the state of their own glass artifacts.

But for now, Loew said the aging problems with the flutes, paired with unknown history about how the artifacts were stored before the Library of Congress received them, sometimes leave the researchers with more questions than answers.

“There are a great number of questions we’re just beginning to ask,” Loew said. “The more you get into it, the more complicated it becomes.”

Annie Dobler contributed reporting.