Rick Sear | Hatchet Designer

Source: Universities’ 990 Forms

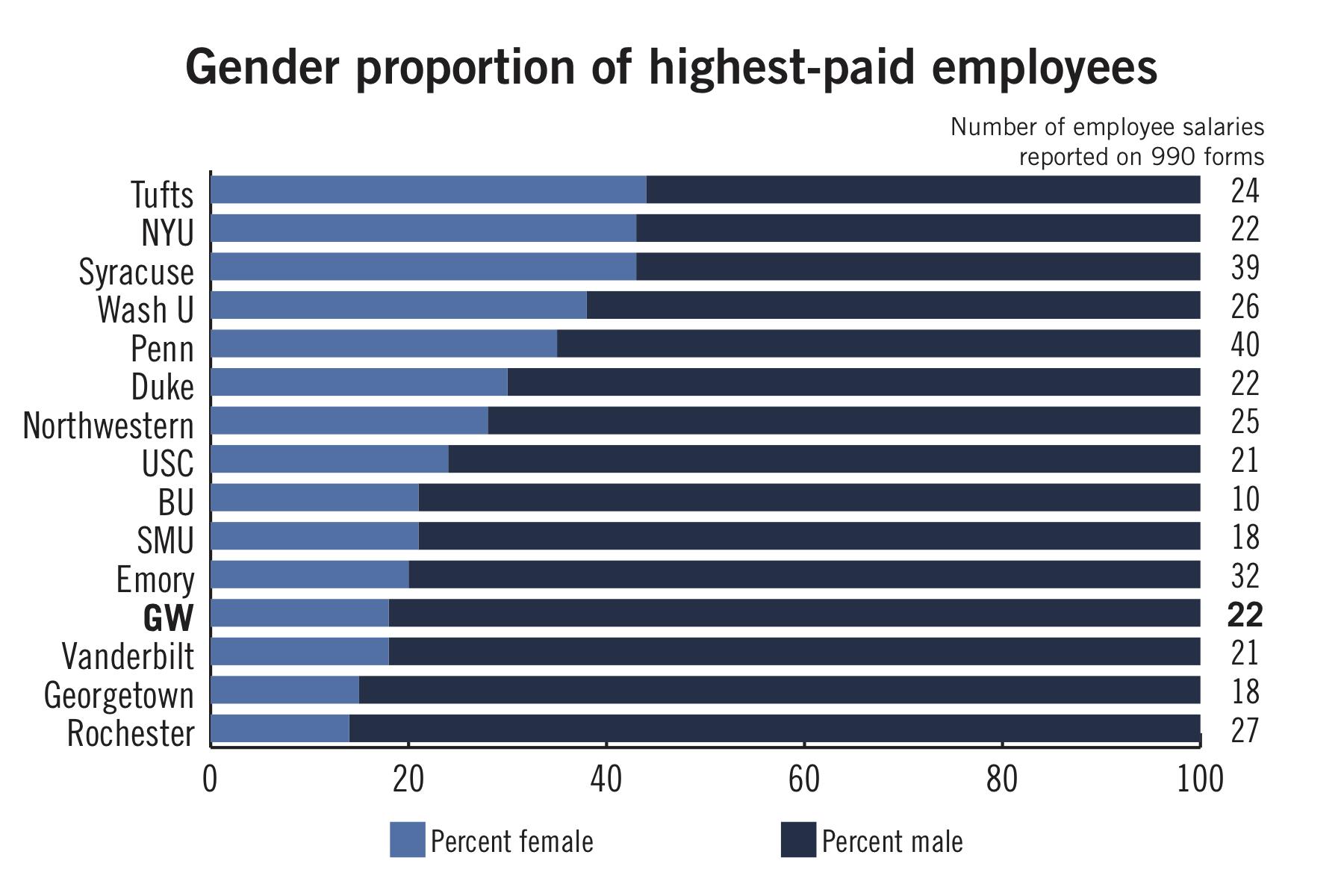

Four women were listed among 22 of the highest-paid employees at GW in fiscal year 2016, a lower percentage of female top-earners than at most peer schools, according to an analysis by The Hatchet.

About 18 percent of the highest-paid employees at GW were women in fiscal year 2016 – the most recent year for which data is available, according to the University’s 990 tax form. The University lags behind many of its peer schools, where an average of about 27 percent of top-earners are female employees, according to 990 tax forms at those universities.

Diversity experts said the underrepresentation of women in top positions is part of a broader trend in higher education – and most industries – and can leave female employees left out of important decisions made by top administrators.

The University’s federally mandated 990 tax form lists the “highest-compensated employees” at GW, a list that includes senior officials like the University president and provost, high-ranking deans, the former men’s basketball coach and some former employees.

Tufts University has the highest-percentage of top-paid female employees. Eleven of the 25 highest-paid employees are women at Tufts, according to tax documents.

Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Editor

Source: Universities’ 990 Forms

Only the University of Rochester and Georgetown University had a lower percentage of female top earners than GW, according to the analysis.

The analysis includes 14 of GW’s 18 peers schools, the only universities where a copy of the most recent 990 form could be obtained.

The analysis of peer universities shows that GW struggles to attain equal gender representation in top positions, even as officials have boosted racial diversity in top posts in recent years. Three of the GW’s nine vice presidents are women, and three of 12 deans are women.

Former business school dean Linda Livingstone left the University last spring to lead Baylor University. She was not listed on the tax document.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said the compensation of senior level employees is reviewed by senior officials and sometimes by the Board of Trustees based on “the prevailing market rate, experience and the qualifications that an employee brings to the job.”

“Diversity is a core value of the University, and that commitment to diversity is evidenced by our recruitment practices for new employees at every level,” she said in an email.

She said the 990 tax form “does not provide a complete picture” of University administrators because employees who appear on the “highest-compensated” list must follow “narrow categories and subjects” set by the Internal Revenue Service and that administrative titles and positions vary across universities.

Csellar declined to say what the IRS categories and subjects were. The tax form is the only public document that lists compensation for top employees at GW.

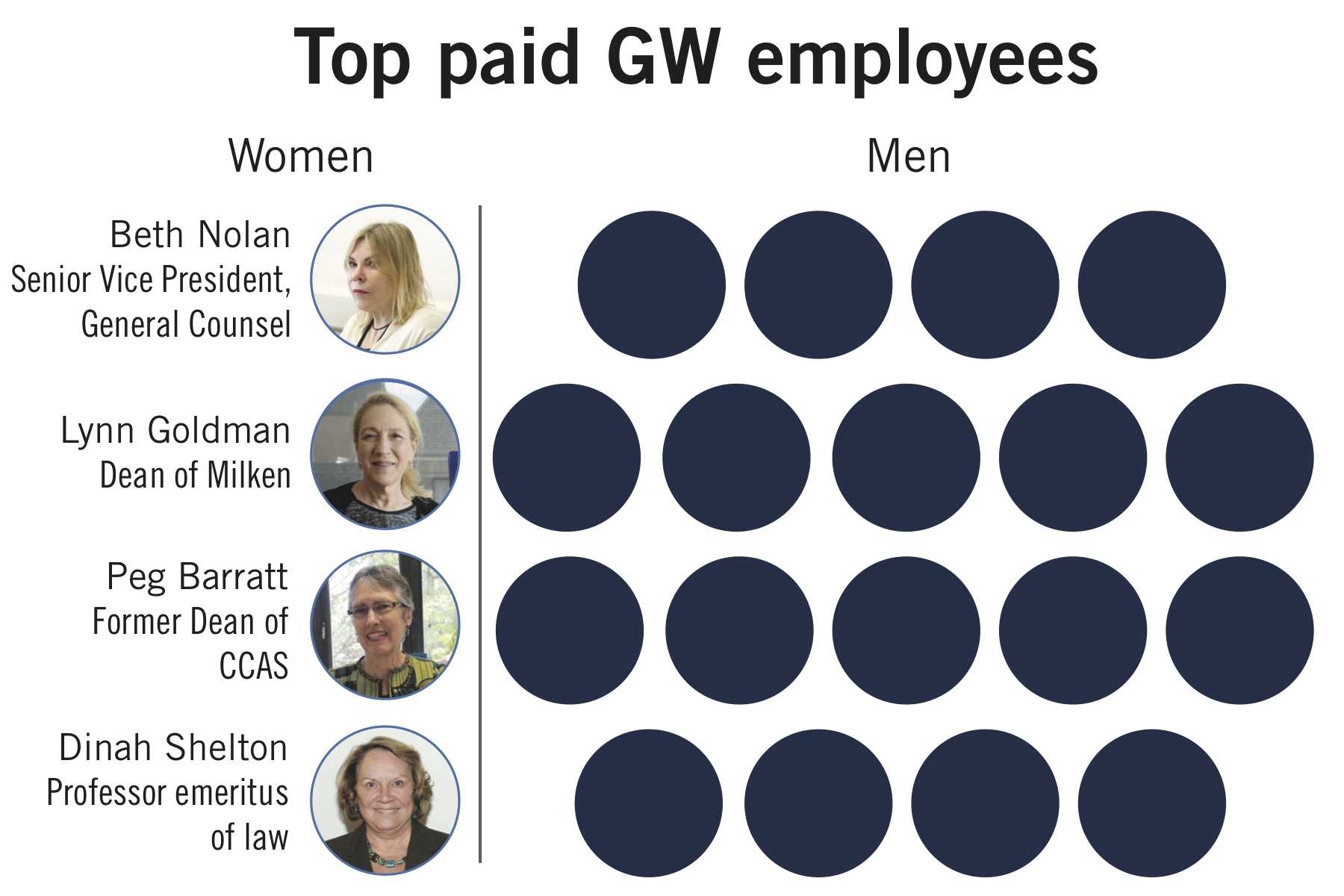

Peg Barratt, the former dean of the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences; Dinah Shelton, a professor emeritus of law; Lynn Goldman, the dean of the Milken Institute School of Public Health and Beth Nolan, the senior vice president and general counsel, were the four female employees listed on the tax form in fiscal year 2016. Shelton and Nolan were in the top ten of highest-paid employees.

Nolan is the highest-compensated female employee at the University, making $681,781 in fiscal year 2016, according to tax documents. She is the fourth-highest-paid of 14 administrators at peer schools in the same position.

The number of women on the list of highest-compensated employees at the University increased in fiscal year 2016 after just two employees made the list in each of the previous four years.

Susan Albertine, senior scholar at the Association of American Colleges and Universities, said the increase wasn’t reflective of an overall trend at the University because it was relatively small and only occured for one year.

“Even if you’re going to say there’s an increase of two, that seems pretty pathetic,” she said.

Nationally, progress for women in senior positions in higher education and many other industries has plateaued, Albertine added. Across all colleges and universities, the percentage of female chief academic officers increased from 40 percent in 2008 to 43 percent in 2013, according to a 2016 report from the American Council on Education.

Because many campuses have made increasing diversity a major goal in the last several years, she said many in higher education have become complacent.

There is still work to be done for women to be equally represented in leadership positions, she said. If more women are represented in senior leadership positions, Albertine said a university’s decisions will be more reflective of the campus community.

“A lot of institutions are assuming they are doing just fine,” she said. “We need some consciousness raising.”

Kelly Ward, the vice provost for faculty development and recognition at Washington State University, said female administrators struggle to move up in higher education because they often lack the mobility of their male counterparts. If women begin raising children, they often are not able to move to different institutions to climb the ranks in higher education, Ward said.

But general sexism present in any workplace is also an important consideration, she said.

“There’s some people who talk about how higher education is based on a monastic tradition that is pretty hard breaking into,” she said. “There’s still a lot of old ideas about perceptions on what women are good it.”

Women in higher education often don’t start their careers aspiring to become deans or other senior leaders because of societal expectations, Ward said.

“Women more often than men will sort of talk themselves out of it then talk themselves into it,” she said.

Lynn Pasquerella, the president of the Association of American Colleges and Universities, said stereotypically male authoritarian or “strong” leaders are still valued in the workplace, but women tend to be more collaborative and focused on consensus-building, making it easier to bridge ideological divides between leaders with opposing viewpoints.

“As long as that’s devalued, it will be difficult for women to take on leadership roles,” she said. “To build bridges across divides is in fact more important than ever.”

Liz Konneker and Annie Dobler contributed reporting.