Updated: Oct. 16, 2017 at 3:01 p.m.

As hiring of tenure-track faculty slows, some long-time professors said they fear a growing number of new professors will have fewer job protections and less academic freedom.

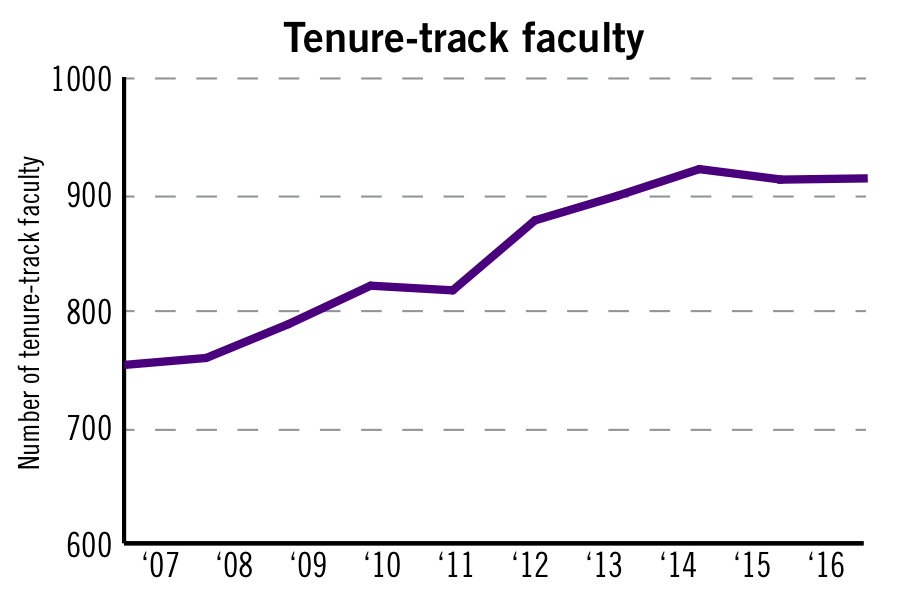

The growth of non-tenure track faculty – adjunct and part-time professors – has outpaced tenure-track faculty each year since 2013. Last year, the number of tenure-track professors at GW increased by just one after a decline in the previous year. Senior faculty expressed concerns that fewer tenure hires will undermine academic freedom and leave new hires with fewer job protections and research opportunities.

As of 2016, the University has 913 tenure-track and 558 non-tenure-track faculty. Between 2011 and 2014, the number of active tenure-track professors increased by between 21 and 60 new positions each year, but fell by nine positions in 2015 and rose by just one last year, according to institutional data.

Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Eidtor

Source: GW Institutional Data

At the same time, the number of non-tenure track faculty – who typically have less job security and work for lower pay than tenure-track professors – has increased by 92 since 2012 and grown each year over that span.

Provost Forrest Maltzman said the Board of Trustees, which approves new tenure-track lines, has no plans to reduce the number of tenure lines, but he said “significant ongoing growth” of these positions is “unrealistic” without an increase in University revenue to make those hires.

The University has traditionally relied on tuition revenue to fund about three-quarters of its budget, but in recent years that revenue has been restricted as officials sought to limit tuition increases and struggled to manage on-campus enrollment caps included in a development agreement with D.C.

Officials have turned to philanthropy to compensate, using the $1 billion fundraising campaign – completed last summer – to fund 23 new endowed faculty positions.

Maltzman said each tenure-track hire is the equivalent of a $3 million to $5 million commitment from the University, an expense the Board must carefully consider.

Maltzman said attracting top researchers, a major University goal for the last decade, depends in part on tenure-track hiring. The Board gives officials the ability to decide which departments are in most need of tenure-track faculty and determines faculty hires based on those evaluations, he said.

“My job is to work with the deans to make sure that we are allocating tenure-track lines in a way that is most strategic and is meeting changing student demands and is part of our research mission,” he said in an interview last month.

Some faculty said trustees should recognize that tenure-track lines allow faculty to pursue research and career interests and improve the University’s academic reputation.

Henry Nau, a political science and international affairs professor in the Elliott School of International Affairs, said most faculty recognize the importance of managing the budget, but trustees may be overlooking the importance of tenure-track positions to the University’s academic mission.

“Tenured faculty are the heart of a great university,” Nau said. “To attack expenditure costs by getting rid of faculty sends all the wrong messages, like we’ve given up being a first-class university.”

Nau said the Elliott School’s reputation as a top international affairs school can be attributed to the growth in tenured faculty shortly after the school’s founding in 1988. Since 2014, the number of active tenured or tenure-track faculty in the Elliott School has grown by one professor, though the number of non-tenure track professors in the school has remained unchanged over that span, according to institutional data.

Nau said the slowing of tenure hiring could impact University President Thomas LeBlanc’s goal of improving the campus culture because it means officials will be hiring more non-tenure-track faculty who don’t have the same job security and can’t easily challenge administrators.

Jeffrey Cohen, a professor of English, said the University has not reauthorized the hiring of a tenure-track faculty position in American drama to fill the vacancy left when a senior faculty member in the department retired last spring. He said the number of faculty in the English department has been shrinking since 2009.

“Tenure is an institutional commitment with that faculty member, but it should go both ways,” he said. “Tenure is also a faculty member’s commitment to the school.”

The bonds students forge with tenured faculty often give students their strongest connections to the University, which encourage alumni donations later on, he said.

The University has historically struggled to move past tuition reliance, and administrators have focused on increasing alumni giving to fund campus projects.

Katrin Schultheiss, the chair of the history department and member of the Faculty Association, said her department plans to hire a tenure-track professor this year, but the University cannot grow as a vibrant institution without more tenure-track hires in in-demand disciplines.

“It’s one thing if maintaining current tenure-track faculty numbers is a short-term measure, but if this is a long-term policy of either freezing or reducing tenured faculty then that’s something that would be really alarming,” she said.

While GW’s tenure hiring has slowed, experts said many universities across the country have actually reduced tenure lines to cut costs. Experts said those decisions may hinder academic freedom because adjunct and part-time faculty sometimes don’t have the same expertise as tenured faculty and often don’t pursue their own research projects.

Risa Lieberwitz, a professor of labor and employment law at Cornell University and general counsel for the American Association of University Professors, said across the nation a majority of teaching is being done by non-tenure-track faculty, a reversal from years past when campuses were dominated by tenured faculty.

At GW, tenured and tenure-track faculty still far outnumber non-tenure track professors, comprising 78.5 percent of active faculty.

Lieberwitz added that a university moves away from its mission to educate and instead focuses on profit-oriented goals when administrators eliminate tenure-track positions. She said universities are weakening academic freedom to make more funding available.

“Eliminating tenure-track is part of the privatization of the University,” she said. “The limiting of tenured faculty makes the University look more like a corporate system.”

This post was update to reflect the following clarification:

The Hatchet reported that the Board of Trustees approves tenure-track hires. While the Board approves the number of new tenure-track lines that will be available, individual schools are responsible for directly hiring faculty.