When Thomas LeBlanc arrives this summer to be the next president of GW, he will have at least one thing in common with all his predecessors – he’s a white man.

In its entire 196-year history, GW has never been led by a non-white or female president. But with increasing diversity as a top priority for officials, particularly during the presidential search, some faculty and students said they hoped this president would be different.

Diversity experts said selecting a woman or someone from a diverse background would have affirmed GW’s commitment to supporting minority communities, but officials said it was more important to select a candidate with a commitment to diversity, rather than to choose someone based on their race, gender or ethnicity.

Some continue to push to learn more about who almost was GW’s next president, but search leaders are declining to provide more detailed information about the pool of candidates.

A diverse but anonymous pool

Nelson Carbonell, the chairman of the Board of Trustees and a member of the presidential search committee, said the committee assessed a “very high quality, diverse pool of candidates.”

“I was extremely pleased with the ethnic, gender and professional diversity of the candidates. We received more than 100 nominations and were fortunate to have a very strong candidate pool representing a wide range of backgrounds and experiences,” he said.

Student Association President Erika Feinman, who also served on the committee, agreed, saying the pool of presidential candidates was diverse “in every way – race, gender, sexual orientation, type of degree, geographical origins and religion.”

Carbonell declined to name any of the candidates under consideration besides LeBlanc, citing the confidentiality of the search, and declined to provide specifics on how diverse the pool was, like saying how many high-level candidates were from minority backgrounds or were female.

Ellen Costello, the associate director of the physical therapy program in the School of Medicine and Health Sciences and member of the Faculty Senate, said the committee should have shown the campus community that they prioritized diversity by releasing the number female or minority candidates who were in the final pool of applicants.

“I think that would make people feel comfortable that the effort was made to look for all qualified candidates for the presidential position,” she said.

Costello said she felt LeBlanc was qualified for the position, but said having a woman lead the University would have been personally exciting.

“I think people like to see a leader that they can relate to, whether from a gender perspective or an ethnicity perspective,” she said.

Looking to diversify

Furthering diversity and inclusion on campus was one of the central tenants of the presidential profile, a document released at the start of the search that laid out the priorities and qualifications of the presidential search.

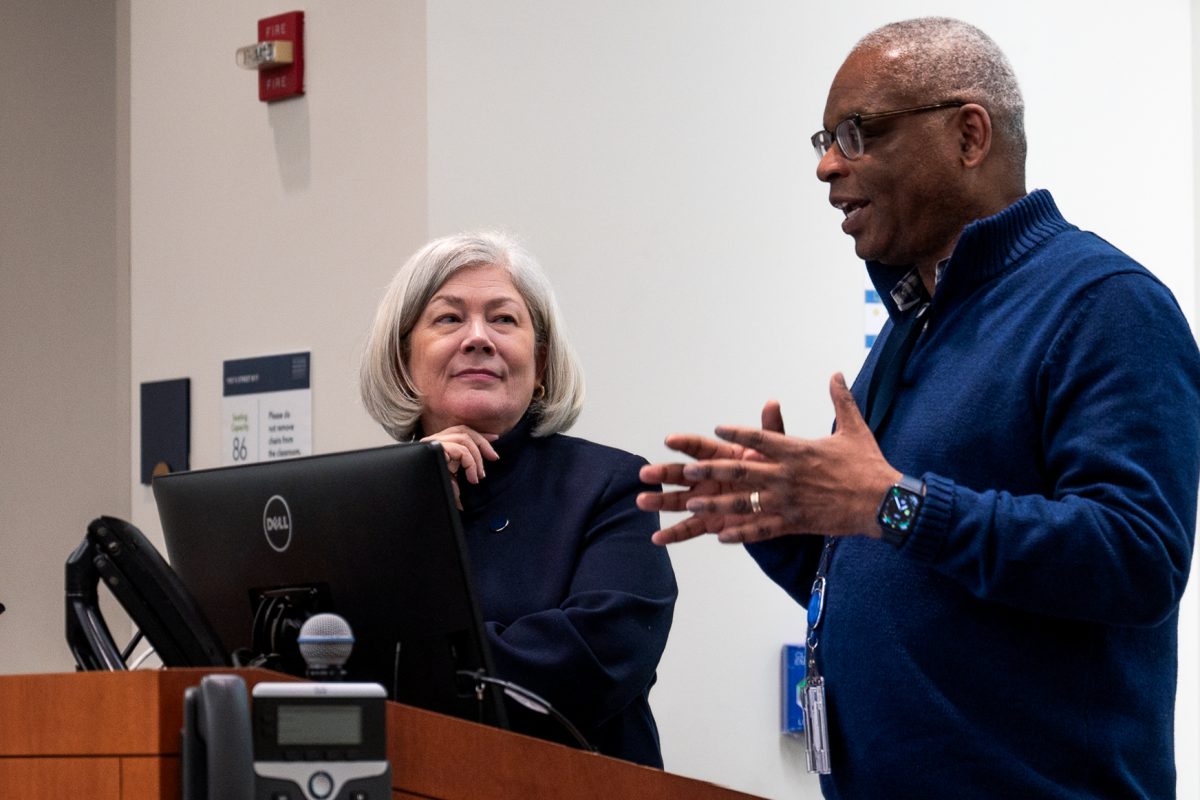

Charles Garris, the chair of the Faculty Senate’s executive committee and member of the presidential search committee, said he believes that many people at the University “would have been happy had the selection been a woman or minority.”

Garris added that diversity was a top priority for the search committee, but that they were more focused on making GW as a whole more diverse and ensuring any presidential candidate shared that goal.

The search committee that initially nominated LeBlanc drew many complaints because it had a six-member faculty contingent in which all members were white and all but one were male. Garris, however, said it was a “very diverse group” due to the 13 non-faculty members.

At the University of Miami, LeBlanc helped institute policies to increase diversity. About 26 percent of undergraduates at Miami identify as Hispanic or Latino, compared to GW’s 9 percent, according to enrollment data from both institutions. Last year, the Princeton Review named Miami the No. 4 school in the nation for race and class interaction.

Garris said he believed that LeBlanc would prioritize bringing more minority students to GW and, more importantly, would ensure that they had the support they needed on campus.

“Minority students are going to find a very strong friend in Thomas LeBlanc,” he said. “They are going to find that he is very receptive and the door is always open.”

In recent years, administrators have made increasing diversity a major priority in recruiting students. They expanded scholarships to District high school students and switched to a test-optional admissions policy, which officials credited with helping to make this year’s undergraduate freshman class the most diverse in the University’s history.

University leaders have also sought to increase diversity of faculty and senior leadership, incentivizing departments to hire more women and minorities by covering half of their salaries for three years from the central budget, but that effort has stagnated recently.

Officials have also sought more women and minorities for high-level administrative positions.

A broader problem

Just 26 percent of college presidents in the United States are women, despite women making up 57 percent of student populations, according to a 2012 study by the American Council on Education. Only 13 percent of presidents come from racial or ethnic minorities, the study found.

American University, one of GW’s peer institutions, announced its first female president Thursday, former Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell.

Natasha Kumar Warikoo, an associate professor at the Graduate School of Education at Harvard University and an expert on the relationship between education, diversity and campus culture, said women and minorities often don’t get named to top positions in higher education because they aren’t groomed for them as much as white men are.

“The pipeline, the extent to which people are being cultivated to these top positions affects who is available,” she said. “You can’t search for people that haven’t had the training and don’t fit the profile that you are looking for.”

Darnell Cole, an education professor at the University of Southern California and an expert on campus diversity, said in an email that a non-white president can be a “role model” for minority students and can make it easier for officials to respond to controversial issues surrounding diversity.

Still, Cole said having a minority president does not automatically lead to a better campus climate, and any president would need to have support from senior administrators and the board of trustees to make significant progress.

“It usually has an impact of policy and institutional priorities for thinking critically about student faculty and staff diversity related issues,” he said. “A lack of such leadership produces at best a gap in institutional priorities that aren’t attentive to the diverse constituencies and larger societal context in which institutions say they lead.”