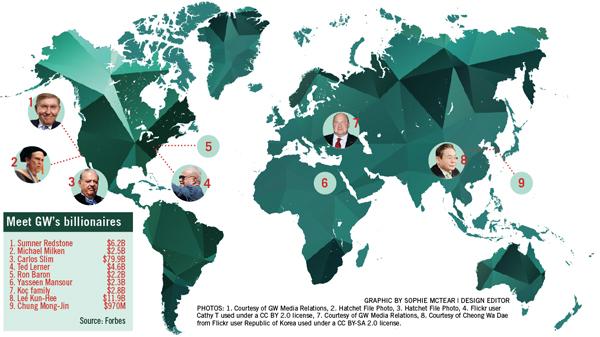

They’re ultra rich, they have money to burn and their gifts could transform GW.

The University counts at least six billionaires among its alumni network, including the chairman of Samsung and a man who owns every McDonald’s in Egypt. As officials seek naming gifts for schools and buildings across campus, those alumni will likely appear on GW’s donor short list.

University President Steven Knapp spent a week in Turkey this month, putting in face time with the country’s richest family and touring a university founded by the grandfather of billionaire business school alumnus Mustafa Koç. But what could come of that relationship is much more than a study abroad program.

Knapp’s budding connection to Koç is a “thoughtful way” to bring him closer to GW, said Josh Newton, the president and chief executive officer of the University of Connecticut Foundation. Koç graduated from the business school’s master’s program in 1984.

“If that person wasn’t being considered a prospect for the business school, I’d be surprised,” Newton said.

The University declined to say whether Koç or any of GW’s other billionaire alumni have donated, though Knapp said the Koç family, which has opened a hospital and museum in Istanbul, is “very active in philanthropy.”

Making that trip to Istanbul could help Knapp make Koç one of GW’s most generous donors. Knapp, who makes several international trips a year, said each is a chance for him to connect with alumni, meet parents and court potential donors.

“When I go to these countries, it’s never just one event – the idea is to get as much as we can done in that period of time,” Knapp said. “We steward our resources so that we make sure when I do go on a trip, it’s been well-prepared for. I don’t go to another country unless many people have been there before me, preparing the ground and making connections.”

Meet GW’s billionaires

The University could choose from well-connected alumni when it looks for billionaire donors, like former trustee Ted Lerner, who now owns the Washington Nationals. Lerner earned his law degree from GW and amassed his about $4 billion fortune through real estate deals. His name is now on the University’s fitness center.

But GW also has ties to international billionaires like Lee Kun-Hee, the South Korean chairman of Samsung. When Kun-Hee studied in the business school’s master’s program but didn’t finish, he was awarded an honorary degree. With an estimated net worth of about $12 billion, Kun-Hee is Korea’s richest man and is nicknamed the “Korean Steve Jobs.”

Knapp said keeping up relationships with alumni overseas can be difficult, but that Korea is one of the countries he visits most frequently.

International business professor Yoon-Shik Park served as a board member of Samsung for 12 years and said Kun-Hee is one of his “very close friends.” He even let Park stay in his family home when he worked as an adviser to Kun-Hee’s family and lived in Seoul.

Park said Knapp has never met with Kun-Hee, but former University President Lloyd Elliott hosted Kun-Hee when he gave a talk at the business school. Park said conversations about a potential donation from Kun-Hee are “very sensitive.”

“The money is no problem but he is so well known in Korea that if he gave a big donation to an overseas university, then the public opinion would be, ‘Why don’t you give more money in Korea to the poor people?’ We are taking time,” Park said. “He is such a generous man and he gave a lot of donations to universities in Korea. I think he will give eventually.”

The University’s other billionaires include a GW Law School alumnus who has earned more than $2 billion through his money management firm, and a South Korean manufacturing magnate.

[RLBox]

[RL articlelink=”https://www.gwhatchet.com/2014/06/10/university-to-officially-launch-landmark-fundraising-campaign/”]

[RL articlelink=”https://www.gwhatchet.com/2014/09/15/alumni-weekend-where-the-gifts-just-begin/”]

[RL articlelink=”https://www.gwhatchet.com/2014/10/13/fundraising-chief-steps-down-leaves-legacy-and-1-billion-campaign-behind/”]

[RL articlelink=”https://www.gwhatchet.com/2014/10/19/university-raises-605-million-in-massive-fundraising-campaign/”]

[/RLBox]

GW’s competitor schools have even more ties to the ultra-rich. The University of Southern California has more than two dozen billionaire alumni, and Duke and New York universities both have about nine, according to Forbes.

Billionaire connections can start a donating domino effect. Schools often look to their richest alumni to introduce officials to other potential big donors, said Nancy Peterman, a partner at the fundraising firm Alexander-Haas.

“Those who know this individual and trust his acumen could look at it as an example,” she said. “I’m sure there are hopes [they would] introduce people to the president and academic leaders, hopefully to lead to other gifts.”

Over the past five years, GW’s fundraising office has also been successful at pulling in gifts from billionaires without a strong tie to the University. GW honored telecom billionaire Carlos Slim with an honorary degree and invitation to speak at Commencement in 2012, and Slim started a program to give full-tuition scholarships to top graduate students from Mexican universities.

Last spring, Michael Milken and Sumner Redstone – who are not alumni – gave a combined $80 million to the public health school, GW’s largest-ever gift, after a Board of Trustees member helped connect them to the University.

Laying a concrete foundation

Knapp recently went to London and said he will also visit China and Morocco over the next year. He said before he meets with alumni or potential donors in a country, he spends a few days “touring cultural sites and learning about the history” to build up a set of solid talking points.

“I do that so when I’m talking to people, it will be clear to them that we have a real interest in them and we’re not just coming there to talk about us,” Knapp said. “You’ve got to have intelligence ahead of time so when you have the conversation, it is focused on the right subject.”

That groundwork is important if GW wants to get a big donor gift. Experts say landing large donations can take years of discussion between the potential donor and the development office, the head fundraiser and eventually the president.

For example, for three years leading up to his gift, Milken met with Knapp and other top administrators at dinners on campus, conferences across the country and a 650-person alumni event in downtown Manhattan.

Knapp’s visit to Istanbul, where he toured the Koç museum and ate lunch with Koç and his father, could also help build that kind of a lasting connection, which experts say is crucial before asking for a big gift. Koç met Knapp when he was a guest speaker on campus several years ago.

Knapp’s relationship with the Koç family began when he met Koç’s billionaire father at Johns Hopkins University, where Knapp served as dean and provost and the patriarch earned his degree. The Koç family made its multi-billion-dollar fortune through the family-owned conglomerate Koç Holding.

To keep that momentum going, business school Dean Linda Livingstone will visit Turkey next year, and staff in GW’s development office already make frequent visits, Knapp said.

The schools most successful at landing eye-popping gifts from prominent alumni start laying the foundation before people make their fortunes, said Richard Ammons, a senior consultant at the fundraising firm Marts & Lundy.

“You may not know they’ll be a billionaire or some highly influential person. A college needs an overall strategy for engaging its alumni because it never knows who will wind up being of a particular usefulness two or 10 or 15 years down the road,” Ammons said.

GW has only recently achieved major fundraising success and still has low alumni donation rates. Schools that haven’t kept up connections by the time alumni make their fortunes may miss out on getting a gift, Newton said.

“You can honor an alumnus with coming to speak on campus or giving them an honorary degree to re-engage them. But I think they’ll see right through that,” Newton said. “All of that is useless if you haven’t nurtured the relationship with that person over time.”

And as officials look to replace chief fundraiser Mike Morsberger, who left the University earlier this month, they can use that search to find someone capable of landing more gifts from billionaires.

Before Morsberger helped secure the Milken gift at GW, he landed Johns Hopkins University a $150 million naming gift from retail billionaire Sidney Kimmel.

Newton, who was previously a fundraiser at GW competitor Emory University, said the top fundraiser must come to a school with a track record of pulling in large gifts.

“The person doesn’t end up at the senior level unless they’ve had some success,” Newton said.