A group of economics professors fear they could lose control over the curriculum in one of the University’s fastest-growing departments if they continue to lean heavily on adjuncts teaching undergraduates.

Though GW has historically saved money by hiring more adjunct faculty across the University, economics professors are arguing that the department does not have enough full-time faculty preparing students for upper-level courses.

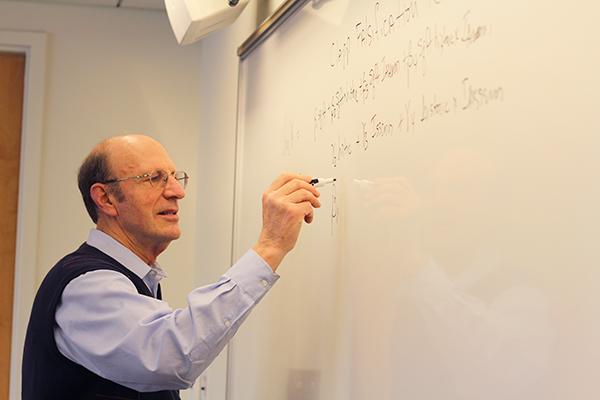

Sixty-one percent of undergraduate economics courses were taught by full-time faculty this year, down from 75 percent five years ago, according to data from the department. Several full-time professors blamed adjuncts for students being underprepared for upper-level courses, in part because being rehired the next year is determined partly by student reviews.

“I’ve had lots of students here who have nothing but adjuncts,” professor emeritus Herman Stekler said. “It really shortchanges the students and isn’t good for their education.”

Because the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences controls the department’s budget and must approve what type of faculty members are hired, professor Anthony Yezer said faculty don’t have many options how they can address their concerns. Their best option would be to refuse to spend the budget allocated by Dean Ben Vinson, he said.

Faculty have never threatened to stop hiring adjuncts before, but professors are so concerned that “we’re reaching that point,” he said.

Yezer said having more adjuncts in a large department also gives students fewer chances to form strong relationships outside the classroom, pointing to adjuncts rarely writing recommendation letters or holding regular office hours.

The conflict comes as the University boasts a growing faculty core, particularly in engineering, public health and hard sciences. Though the Columbian College faces about a $2 million budget deficit due to lagging graduate enrollments, the college had been enjoying an era of growth with 40 new tenure-track positions over the last three years.

Departments like economics, however, are feeling left behind. The number of majors in the economics department doubled between 2007 and 2013, swelling to about 450 majors. Professors say the department has not been approved to create a single tenure-track professor position in the last few years.

Bryan Boulier, deputy economics department chair, said adjunct professors typically do not know how the courses they teach fit into the overall curriculum, so they have trouble preparing students to build upon their courses in future classes.

He also said it is difficult to retain strong adjunct professors because of low salaries. Adjunct professors earn about $4,500 per course while full-time assistant professors make on average about $75,000 a year in Columbian College.

To improve adjuncts’ teaching quality, full-time faculty could make an effort to monitor their lesson plans or exams, Boulier said.

Vinson, who took control of the college last year, said adjunct faculty bring unique perspectives into their classes from their work outside of academia, and that the college supports them as they develop their courses.

“Determining which part-time faculty to hire in a specific department is based on a consideration of the department’s needs and is intended to provide our students with a well-rounded academic experience,” he said in an email.

Other departments, like computer science and statistics, have also seen rapid enrollment growth in the last five years. Those departments have relied on doctoral candidates teaching undergraduates to make up for the influx of students.

At GW overall, spending on teaching overall lags far behind competitor schools – about $10,000 less per student than peer schools. In 2012, GW spent $18,500 per student on instruction, according to data from the Department of Education.

By using more adjuncts, officials can avoid investing the about $2 million it takes to fund a professor’s tenure.

Rick Belous, chief economist for United Way Worldwide and an adjunct professor at GW, said he feels a strong connection to the University, though he may be an exception after getting his doctorate in economics from GW in 1984.

“I take the teaching very, very seriously,” he said, adding that he has a 12-hour turnaround time on emails from students and always has textbook lists to the bookstore on time. “I’m not going to say every adjunct takes it seriously, but a good number do.”

Still, Kerri Evans, a junior economics major, who has taken five courses with adjunct professors so far, said that while standards can vary, she has experienced part-time professors who are interested in making one-on-one time for students.

“Oftentimes I felt that adjunct professors were actually more willing to devote time to students because they seemed truly interested in individual students, whereas sometimes tenured professors seemed more focused on their other classes or research,” Evans said.

– Meredith Stonitsch contributed to this report.